An Accidental Artist

Since childhood, my ultimate career ambition has always been to be a novelist, to craft long-form prose, to see it in hardcover with a removable jacket sleeve, and to somehow sustain myself and my family through the quest of creating memorable fiction. I was told at an early age by a teacher with whom I maintain contact to this very day that I had a talent, that in fact I had “no reason whatsoever not to be a writer,” and this initial encouragement was reiterated by others — teachers, friends, mentors — throughout many years.

I believed what I had been told.

Writing morphed into other creative interests, primarily drawing, but also poetry, music, and painting. Anything with an aesthetic nature flowed somewhat easily. In college I landed the lead in a university’s major production without ever having any acting experience (and managed to land a wife in real life in the process). Years later my wife and I were given full-time jobs in radio without ever having taken a class in broadcasting. Like these, in many of my creative pursuits I’ve stumbled into them rather than actually sought them out.

I have always understood the arts and had an appreciation for movies and novels, in particular. 1989’s Dead Poets Society spoke to my core and resonated on a level I’d infrequently experienced before. I identified in some way with each of the characters and for the next year I almost always had a notebook within arm’s reach to scribble out a stanza when inspiration struck.

Most of the creative endeavors I’ve encountered, I’ve enjoyed. And for the most part I have had a certain level of competency. Not expertise, mind you, but competency, and enough competency to make me think I had a shot of actually transforming one of these artistic pursuits into a genuine career.

But creative writing was the only endeavor that allowed me to relate to the phrase, “it feeds my soul.”

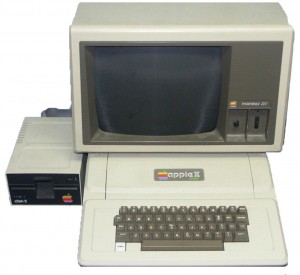

What my first computer looked like, right down to the green screen monitor with the weird film on the screen. Image from http://apple2history.org/

Somewhat surprisingly, my interest in the arts lead to a successful career in the IT industry. I always loved to write and I always liked playing video games. In the early 1980’s my father bought us an Apple II+ computer which, if I wanted to write and and play games, I had to learn to use. Even Applesoft BASIC (and later just regular BASIC) programming had a certain creative sensibility and flow to it. Because of this combination of technical and creative ability, when it became possible to create graphically enhanced websites in the mid-1990’s, I stumbled into an unexpected career that was nothing more than being in the right place at the right time. Anyone could now create a website, but in the early days of mass-acceptance of the Internet, and long before the pervasiveness of WordPress, making a website actually look good was akin to voodoo.

After several years, though, my technical pursuits involved less and less creativity as employers saw in me a proficiency for project management and leading teams. I had children to feed now, and a mortgage, and creative pursuits and the romantic notion of being a starving artist and modern day Bohemian felt selfish.

The Worst Possible Doubt

In 2000 I was several years into a career developing software systems both as a developer and a manager. Struck by inspiration, I’d leave work each night and stop at the local library to pound out 1000 words before heading home. The concept for the story was the fruit of frustration from the myriad of pop sensation novels that revolved around dysfunctional characters living out immoral solutions to their shallow lifestyles. In the midst of writing, as a result of multiple factors, my own relationship with God was deepening. I told myself and God that my novel was an antidote to a literary market filled with tales of dysfunction that was given free reign to destroy lives. As my own story was borne, I daydreamed of best-seller lists and bidding wars and advance checks with multiple zeros. I’d convinced myself that the publication of this novel would alter my life forever.

The end result was a novel called “This Time For Good” which was promptly rejected by over 150 agents and publishers. All the secular publishers said it was too religious, all the religious publishers said it was too Catholic, and the one Catholic fiction publisher at the time said they weren’t publishing any more fiction.

The rejections poured in over the course of a year in which the distaste for my accidental career in IT was magnified with each returned manuscript. I’d arrive home each evening and check the mail before greeting my family. Another rejection letter, and then another. Each morning, before my eyes would open, I would wonder if that was the day everything would change. Would that be the day when a publisher would snatch up my book and I could leave the IT industry behind, the financial security of my family assured as a result of a silly story I’d concocted?

“It’s all I think of all day,” I told my wife. “I can’t stop thinking about it. Literally a minute doesn’t pass where I don’t think about that book being published. Why would God give me these talents, and the desire to give life to these words and these creations if I wasn’t supposed to do something with it?”

My wife had no idea how injurious — and true — the words she would then speak would be to me, how deeply they would wound, and how long the wound would bleed. Having said that, I’m so grateful she had the courage to speak them to one as hardheaded as me.

“It’s as if you’ve made the book a god,” she said, and I was furious at the accusation. Furious not at my wife, but at the mere possibility her words were true. The hours I’d poured into the novel, the sacrifices I’d made to bring it to life. A false god, she said. In the service of God, had I created an idol? Had the pursuit of a supposed good in fact brought life to an evil?

I railed against everything that night, in a way I’m not sure I can adequately describe. For hours, I cried and screamed at God in hushed anger. All I had worked for and toward, all hope of escape from my present work situation, all I had dreamed of for years, it was all lies. My dream since childhood, which seemed so close to reality as I wrote that book, was nothing more than a dream, and I had just woken up to realize it as such.

And on that Friday evening, this book I’d told myself I’d written for God, caused me — for just the briefest of seconds — to actually doubt the existence of God. If all of what I’d set forth to accomplish in my life was lies and misdirection, then perhaps the God I longed to serve was a lie, as well.

And there it was, on the table, for just a moment, a thought I’d never considered.

My family had gone to bed by this time and I remember so clearly exactly where I was standing in the kitchen when that thought was made manifest. I had one hand grasping the kitchen counter to hold myself up against the despair that threatened to overtake me, when I had the thought that if this book, this skill, this talent, and desire, were all false, “Then maybe You don’t exist, either.”

I was immediately remorseful for even thinking it. Of course God existed, but now so did the doubt that all I’d ever hoped to do in life would ever be made tangible. If writing, and more specifically, getting published, had become a god, I wanted nothing to do with it at all. Soon thereafter, I gave up the pursuit of writing completely. If I’d made a god out writing, and especially that book, then I wanted nothing more to do with it. I closed the door on the dream I’d had since childhood.

I was immediately remorseful for even thinking it. Of course God existed, but now so did the doubt that all I’d ever hoped to do in life would ever be made tangible. If writing, and more specifically, getting published, had become a god, I wanted nothing to do with it at all. Soon thereafter, I gave up the pursuit of writing completely. If I’d made a god out writing, and especially that book, then I wanted nothing more to do with it. I closed the door on the dream I’d had since childhood.

Meaninglessness

The arts lost meaning to me. In the grand scheme of things, what did it matter? Even if I did get a novel published, unless I ended up being a bestselling author, what good would it do the world 100 years from now? Suddenly, creativity was an exercise in selfishness, something I’d waste hours on for my own gratification. I may as well just play video games or watch television.

One afternoon, when cleaning out our attic, I threw away three large trash bags of my short stories, poetry, and drawings. Destroyed them for good, forever. Left to mold and decay and disappear buried deep in a mound of trash somewhere.

Yet no matter how I tried to squash it, the need for creativity would not be killed. In the early days of podcasting, I used that medium to create absurd radio plays and parody songs. The more outlandish the better. The podcast was supposed to be for catechetical purposes for our non-profit religious apostolate, yet I couldn’t help myself from doing oddball things from time to time, even though I was completely unaware that all I was doing was feeding the creative part of me that I was simultaneously trying to abandon. That part of me was starving and wanted to be fed.

The podcast lead to a video series, which lead to radio, which lead to a sitcom pilot, which lead to writing two non-fiction books which easily found a publisher. But all these, I told myself, were for the purpose of evangelization. And for the most part, they were. During the same time I taught myself to play piano and continued to play guitar and sing (though admittedly not that well). Some of those initiatives did in fact placate — though not satisfy — my soul in a way fiction and painting once did, but on a very superficial level.

Through it all, despite all those many rejections I’d received on my novel, I still thought of the unpublished novel, of the manuscript that has pretty much been haunting me for the past fourteen years. I can’t get the story out of my head, and I can’t shake the desire to have it professionally published. As I said, I’ve had no issue finding publishers for my nonfiction Catholic works, and those works have sold fairly well, but fiction is a whole other beast. And it is at the heart of what I’ve always wanted in life.

Years later, after making more inroads in Catholic media as a result of our radio show and running several apostolates, a Catholic publisher that doesn’t handle much fiction offered to look at the manuscript and, after reading, suggested that the story was too candid in it’s depiction of one’s struggles with chastity, and in fact that I had written a book with too much sexual tension. As a result, I’ve muddled with ideas of making This Time For Good a gung-ho Catholic novel. Just go full Catholic, for a Catholic audience, chock-full of Catholicity on every page. Delete anything that truly resonates in the genuine struggles people encounter in their relationships and just write a sellable, sterile, predictable love story with the obligatory come-to-Jesus revelation in the third act.

Just preach to the choir from the beginning to the end and be done with the blasted thing.

But I’m not comfortable with that for a few reasons, primarily because so far there has been no proven market for Catholic fiction, so why write for a barely existing audience?

And there’s the crux of my problem from the very beginning: I love literature. I love to write. I love to create. But at the heart, I don’t see worth in creating unless there’s some sort of satisfaction of compensation at the end. Compensation, I suppose, equals affirmation of one’s talents. You wrote something so dang good I’m going to pay you for it.

But then recently I read in Pope John Paul II’s 1999 Letter to Artists that, “Artists who are conscious of [the tasks they must assume, the hard work they must endure, and the responsibility they must accept] know too that they must labour without allowing themselves to be driven by the search for empty glory or the craving for cheap popularity, and still less by the calculation of some possible profit for themselves.”

This brings me great pause. So…I’m to create for the sake of creating? I must endure, to labor, not for affirmation, and certainly not for profit?

That stinks, man.

I read that as “create for the sake of creating and for the sake of sharing the creation, but don’t plan on getting paid for it.”

Trust me, I don’t anticipate payment, but why waste even more time on a novel I’ve already invested countless hundreds of hours on if there’s no renumeration in the end? That’s the thing that’s always stuck with me.

Haunted

But perhaps I’m not in it just for a buck. Why else have I been so unable to escape the shadow of this story and the characters that inhabit this world? It’s important to point out that this isn’t even my first novel. My first novel was finished in 1993 and was so terrible I have since destroyed every copy. I’ve gotten 200 pages into two other novels. Those books I rarely even think about, but This Time For Good I can’t shake. I have three children who have been in my life for less time than this book has. For a third of my life, I’ve been trying to bring this novel to completion.

A little over a year ago I went back and started reading the manuscript again, toying with making those Catholic changes. And after time away from the world in which I’d so completely immersed myself, what I saw wasn’t impressive. There was too much telling and too little showing. Too many extraneous characters. No overarching character plots. Infrequent set-ups and pay-offs. In short, it was abundantly evident I’d basically vomited words out on paper to get it out of my head, but little of it could ever be considered “literary.” There was a good character-based story, and the two main protagonists really are people I’ve grown to love very deeply, despite their fictitiousness. But the overall tale was pointless.

One day I was sitting in an airport waiting for a flight and for no reason whatsoever, I decided to take just two simple paragraphs and expand them, to dive more deeply into the terrain of the tale and see what I may have missed in the original telling. What came out of my fingertips astounded me. It was writing I couldn’t believe was even mine. Over the fourteen year sabbatical, it was as if the story had been marinating and had grown in intensity and flavor. And once I’d tasted the story again, I couldn’t resist another helping.

Over the last year and a half since that day in the airport, I’ve been drawn back to that chapter time and again. I just haven’t been able to shake this story.

But that question remains. Writing this, or painting a picture, or making a YouTube video. What’s the ultimate point? If I do this, if I write, if I spend time away from the family and staring at a computer screen, what good will any of this bring?

I’ve been wrestling with this as if I’m wrestling a demon. I’ve prayed and asked God countless times to release me from the desire to write fiction, to escape creative impulses. I’ve questioned the need for any hobby at all. And, like any time I fight for understanding, I try to wait until God is ready to speak and reveal.

One evening just two months ago, I followed a compulsion to walk into an arts and crafts store. I stood for perhaps half an hour looking at paint brushes and canvases, remembering what it was like years ago when I first started to paint. I stopped painting after our first child was born, but now something was calling me, another artistic beacon calling out to me. I knew I’d never sell a painting, but I could at least make things to decorate our home. There was a certain rationalization to this particular creative pursuit.

I decided at some point that I’d give painting another shot. I could allow that in my life. But merely opening the door to something purely artistic like painting somehow brought greater life to my struggle with writing fiction. For the next few weeks, both were regularly in my brain. As I pondered what images I might bring to life through paint and canvas, I almost involuntarily kept thinking of the weak areas of the novel and my mind wrestled with solutions.

Shortly before Christmas, I mentioned this struggle on the podcast my wife I and continue to host each week. How could I spend time doing something as selfish as writing or painting at the detriment to my own family, I asked. Is it fair for me to go hide in the basement with paintbrushes or a word processor just to while away the hours?

I mentioned this to a few other people and my good friend and former co-worker Fr. Roderick Vonhogen (he, also, of a creative slant) said something that struck at the heart of all my deliberations. Paraphrasing, he said, “Creativity allows the Holy Spirit to work through us to create something else. In that sense, it could be like a prayer.”

Prayer is something that makes sense. Prayer is something I know I need in order to make it through my hectic days.

Coupling that with John Paul II’s Letter to Artists where he says, “…beauty is the vocation bestowed on [the artist] by the Creator in the gift of ‘artistic talent.’ And, certainly, this too is a talent which ought to be made to bear fruit, in keeping with the sense of the Gospel parable of the talents (cf. Mt 25:14-30).”

This is rationalization I can accept. If I have been given talents, and yet I bury them away and don’t even try to expand them, I’m like the nervous servant who buried the talents entrusted to him.

John Paul II says at the beginning of that letter, “None can sense more deeply than you artists, ingenious creators of beauty that you are, something of the pathos with which God at the dawn of creation looked upon the work of his hands.”

While that line is compelling, the next section, to me, was absolutely captivating.

“A glimmer of that feeling has shone so often in your eyes when — like the artists of every age — captivated by the hidden power of sounds and words, colors and shapes, you have admired the work of your inspiration, sensing in it some echo of the mystery of creation with which God, the sole creator of things, has wished in some way to associate you.”

God may not have called me to be a published novelist, but He “has wished in some way” to associate me with the echo of Him as creator.

Creativity, when brought to life, is an echo of God, and as much as I’ve tried to squelch it these last fourteen years, in is undeniable that he has “wished in some way” to associate me with the echo of Him.

Brush Strokes

For Christmas, my wife got me new brushes and paints and canvases and an easel.

When I sat down before that first blank canvas in so many years, I was struck not with fear, but with a sense of solemnity. And I prayed. I prayed for the Holy Spirit, if He so chose, to work through me to breathe life to something on that white screen before me.

And the first attempt was horrid.

So I started again, and I painted in prayer. This is the result.

For the first time in years, I’m giving into the artistic impulse, and it feels right and good. It feeds on itself in the best of ways and then resonates in other areas of my life. As I write fiction again more regularly (still fighting non-stop daydreams of publication), I find myself energized to approach my actual day-to-day job with a different perspective. I’m giving into the creativity again and asking the Holy Spirit to be a part of it, to help me find worth in it and the time I’m spending in these efforts.

This Time For Good, while adequate when written, was rightfully rejected by more than 150 publishers and agents. As I pondered the many problematic story elements, and for years could develop no solutions, in just the last two weeks the Holy Spirit has broken through in some amazing ways. The story suddenly seems new, while the characters I love so much are even more vibrant. I’ve had to cut out some critical aspects of the story — including other characters I love — but I’m trying to let the Holy Spirit inspire and lead.

And I’m painting, and that slows me down, makes me focus on the details and the shadows and the necessity of multiple layers and growing and building and patience. So much patience. Fourteen years of patience, and perhaps decades more ahead.

And I’m painting, and that slows me down, makes me focus on the details and the shadows and the necessity of multiple layers and growing and building and patience. So much patience. Fourteen years of patience, and perhaps decades more ahead.

I’ve also been thinking of developing a new podcast to explore these things, but perhaps that’s too much too soon. But I’m thinking of a title along the lines of “The Well Fed Artist: Feeding Creativity While Having a Day Job.”

We’ll see if inspiration strikes.